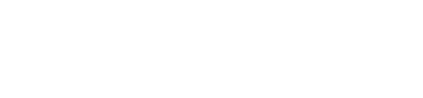

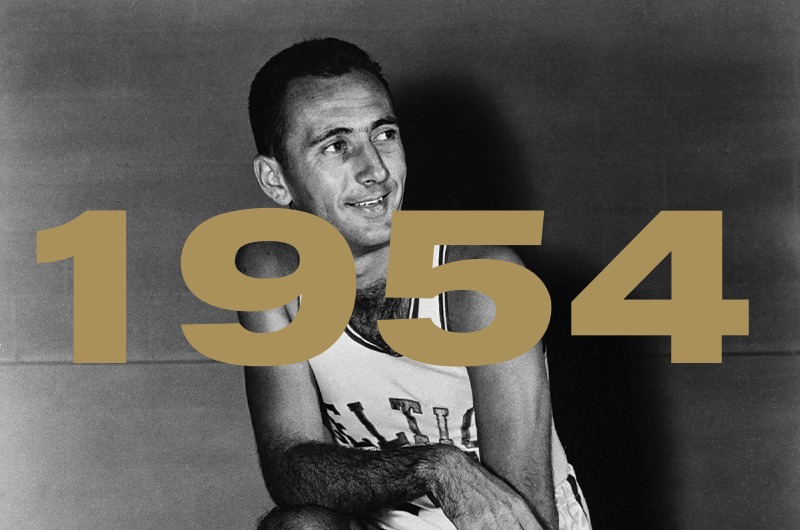

Bob Cousy begins organization of NBPA

In 1954, Bob Cousy of the Boston Celtics began to organize the

players by writing to an established player from each team,

seeking

their input and support for a formal union to represent players’

interests. Soon, the National Basketball Players Association was

created, and Cousy became its first President. In January of

1955,

Cousy went to NBA President Maurice Podoloff with a list of

demands:

payment of back salaries to the members of the defunct Baltimore

Bullets club; abolition of the secretive $15 fine for a

“whispering

foul” that referees could quietly place on players during a

game;

establishment of a 20-game limit on exhibition games, after

which

the players could share in the profits; establishment of an

impartial board of arbitration to settle player-owner disputes;

payment of $25 for public appearance expenses other than radio,

television and charitable functions; and moving expenses for

traded

players. The NBA refused to recognize the union and, of all

their

demands, only agreed to two weeks of back payment for six

Baltimore

players who had played for the club before it folded.

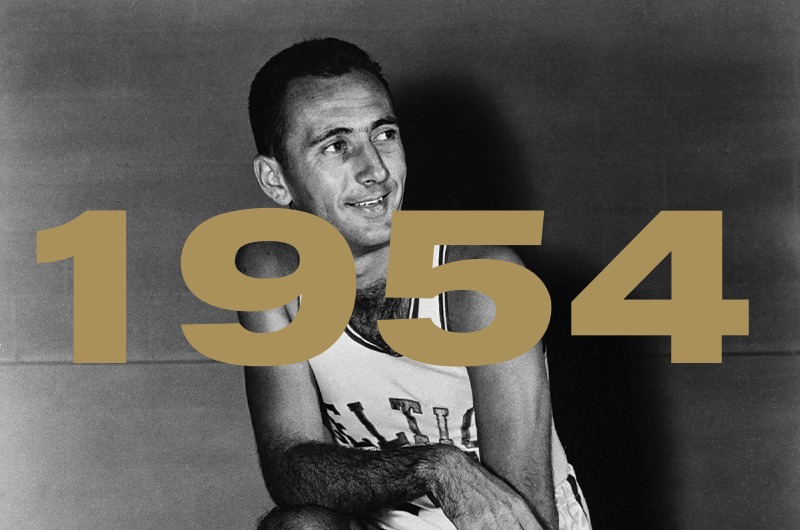

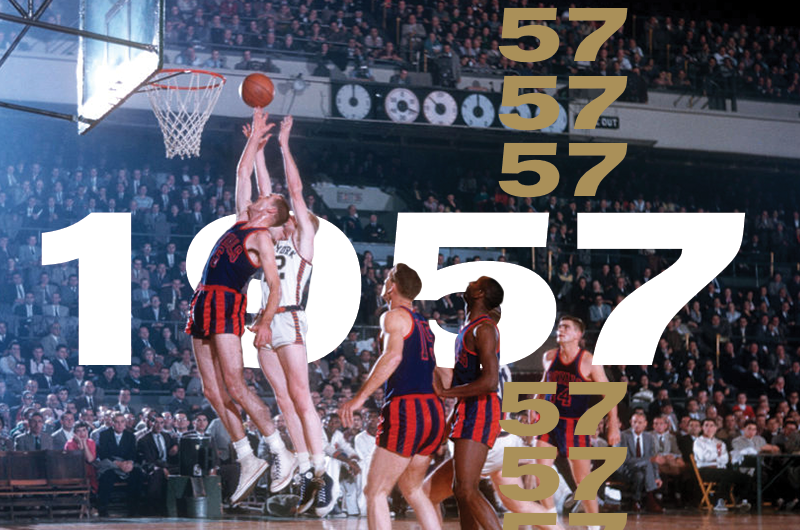

First CBA (after 1955 demands rejected)

It was not until the threat of a strike in 1957 and Cousy meeting

with AFL-CIO officials over possible union affiliation, that the

NBA

entered into discussions with the NBPA. In April of 1957, the

NBA

Board of Governors formally recognized the NBPA and agreed to

their

requests:

- An abolition of the whispering fine;

- A $7 per diem and reasonable traveling expenses;

- An increase in the 1957-58 playoff pool;

- Reasonable moving expenses for players traded during the

offseason;

- Referral of player-owner disputes to the NBA League

President or

a committee of three NBA Governors chosen by the players;

- Elimination of exhibition games within three days of the

season

opener; and

- Regular players not required to report to training camp

earlier

than four 4 weeks prior to the season

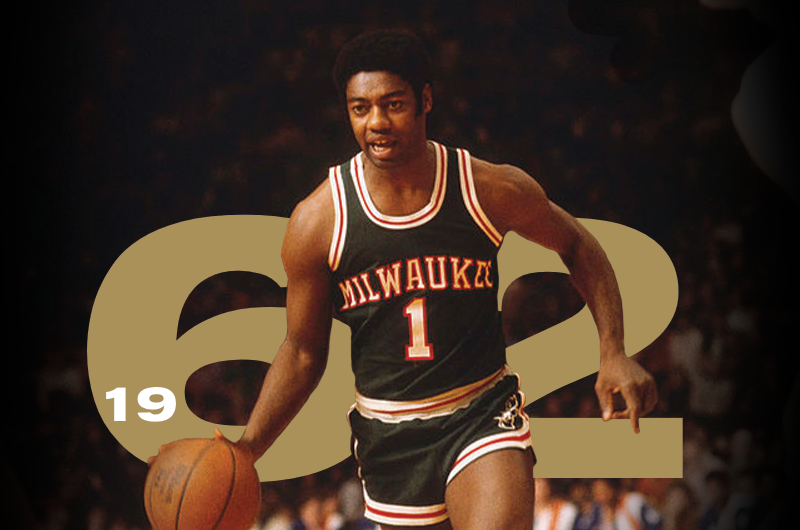

Pension program introduced and union hires first counsel

In January 1961, NBPA President Tom Heinsohn reached an agreement

with the owners over a player pension program with the details

of

the agreement to be worked out the following month. The players

set

a goal of $100 a month for players over age 65 with five years

of

service and $200 a month for players over age 65 with ten years

of

service. Negotiations to finalize the agreement broke down

however,

and in 1962 Heinsohn hired attorney Lawrence Fleisher—who would

remain as NBPA general counsel for the next 25 years—to fight

for

union goals.

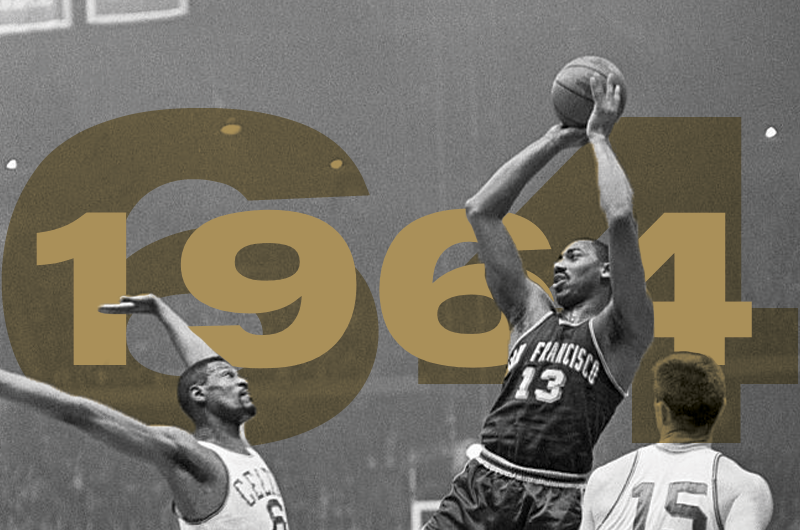

All-Star boycott

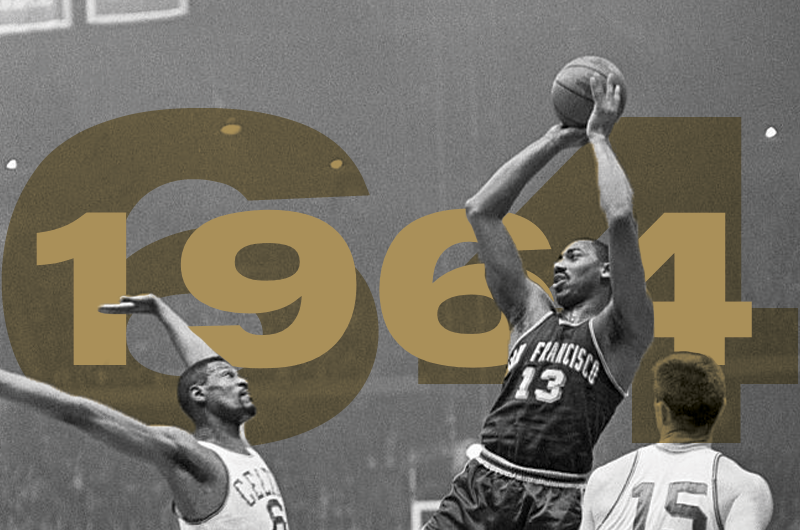

Progress was slow until the 1964 All-Star Game, which was the

first

All-Star Game ever to be nationally televised. Recognizing an

important opportunity to bring about change, the players

threatened

not to play unless certain demands were met. They raised three

main

issues: first, they insisted on the establishment of a pension

plan;

second, they wanted the NBPA to be formally recognized as the

exclusive bargaining agent of the players; and third, they

sought an

increase in the per diem to eight dollars per day. Minutes

before

gametime, NBA President Walter Kennedy personally guaranteed

that a

pension plan would be adopted at the next meeting in May, and

that

the other demands would be met. The game went on – ten minutes

late.

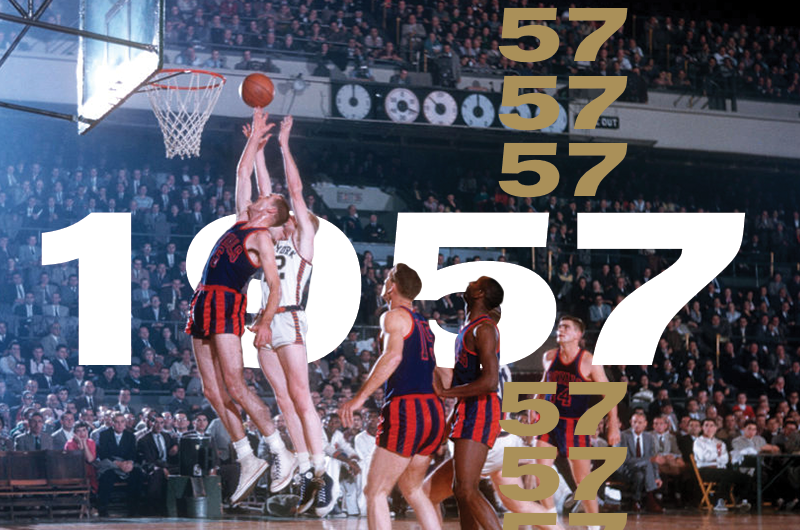

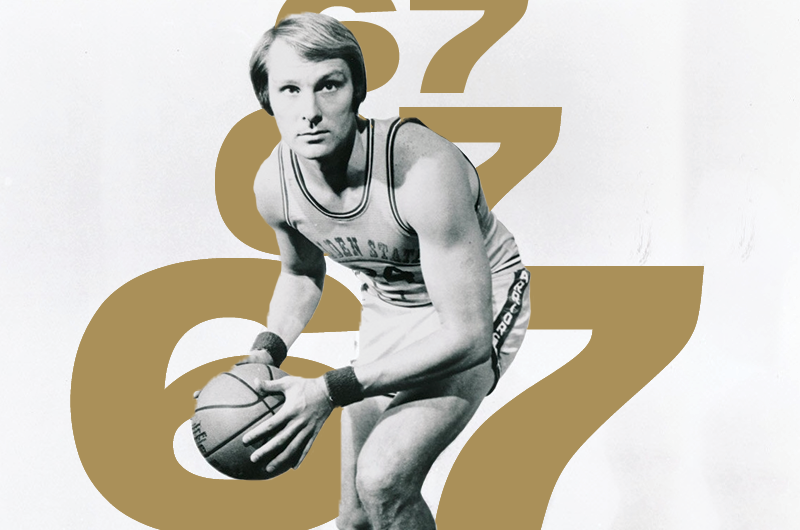

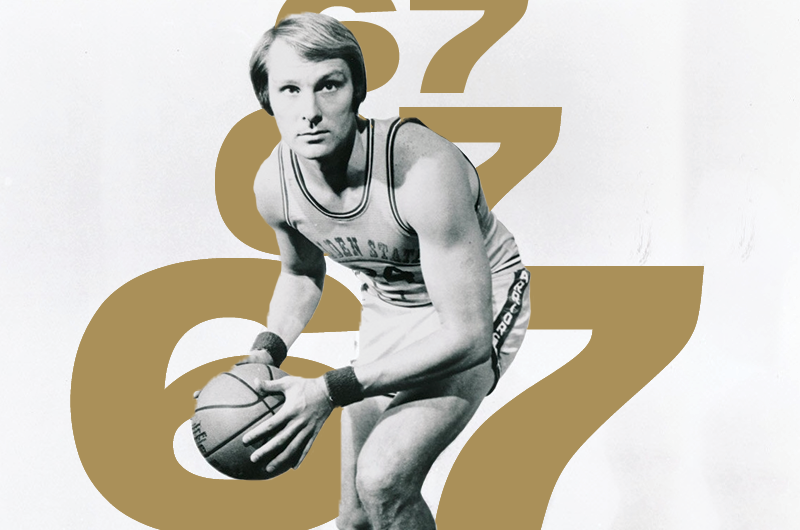

Players seek new terms under Oscar Robertson’s leadership

The great Oscar Robertson of Cincinnati succeeded Heinsohn as

President in 1965 and announced at the 1967 All-Star Game that

the

players would seek new terms; specifically, they would ask the

owners to be paid for exhibition games, to reduce the number of

exhibition games from 15 to 10, and to upgrade the pension plan.

The

players won the following agreement:

- A $600 a month pension plan for all players with ten years

of

service and over age 65

- New medical and insurance benefits

- Negotiations for exhibition game pay

- An 82-game limit on the regular season

- The elimination of games played immediately prior to the

All-Star Game

- A new committee to review the standard player contract prior

to

the 1967-68 season

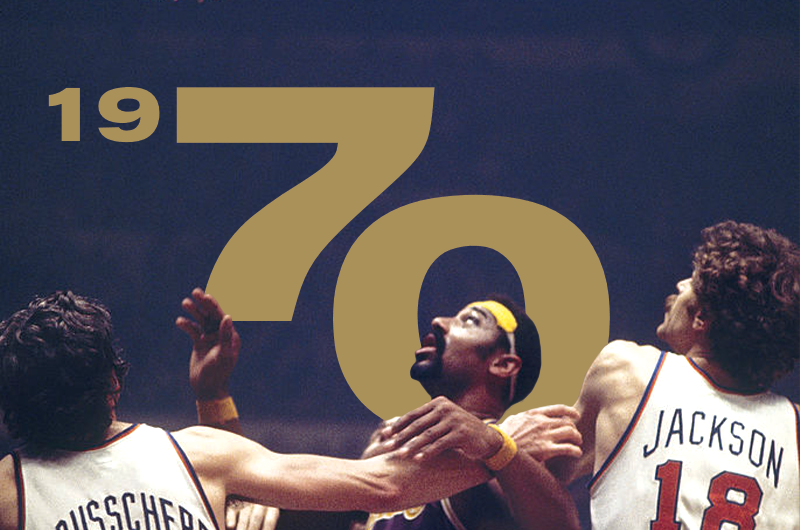

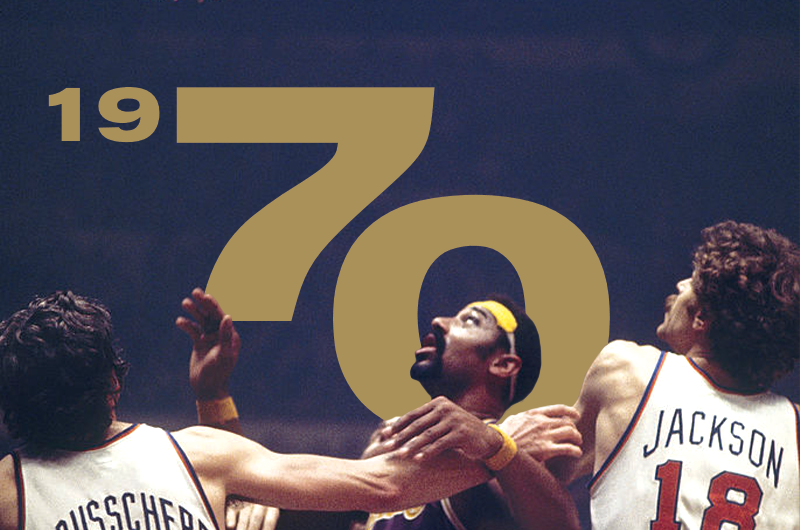

Robertson suit filed (settled in 1976) over NBA, ABA merger

In 1967, the American Basketball Association was formed, and the

new

competition helped cause players’ salaries to rise. Recognizing

this

trend, the NBA soon opened discussions with the ABA over a

possible

merger which would eliminate this healthy competition for player

services. In response, the players filed the “Oscar Robertson

Suit”

under the antitrust laws in 1970. Through the lawsuit, the

players

hoped to block the merger and also ease the burden of various

other

player restraints, including the option clause that bound

players to

a team in perpetuity. The NBPA won a restraining order to block

the

merger, and the owners came to the table, though not before

unsuccessfully attempting to gain Congressional approval for a

merger. New president Paul Silas used leverage from the court

victory to secure a new agreement with the NBA. The new deal

gave

players a limited form of free agency, eliminating the option

clause

in all contracts. In addition, the owners paid 500 players a

total

of $4.3 million as a settlement and the union $1 million for

legal

fees, pending dismissal of the Oscar Robertson Suit. The ABA and

NBA

finally merged, but by that time, the collective bargaining

agreement had brought the players an increase in the minimum

salary

from $20,000 to $30,000, an increase in pension benefits,

medical

and dental coverage, All-Star Game pay, term life insurance, and

a

fair per diem.

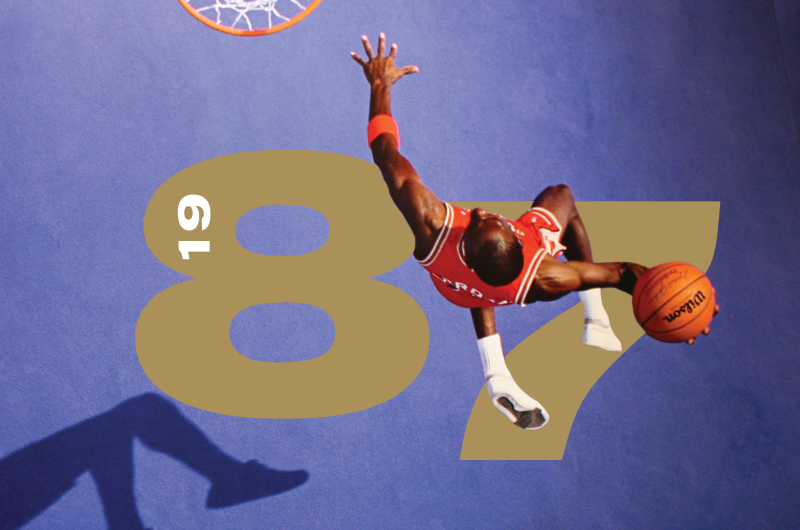

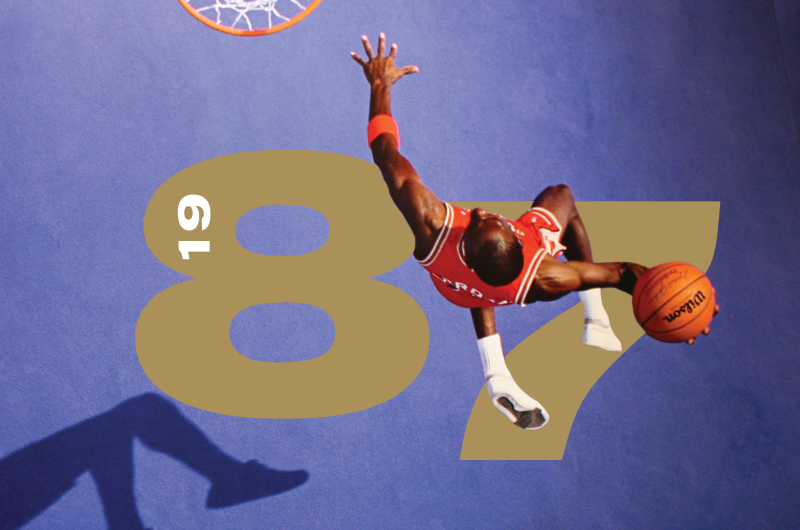

New CBA with revenue sharing and salary cap

In 1983, the players agreed to a landmark four-year collective

bargaining agreement. The lynchpin of the deal was a revenue

sharing/salary cap concept, under which the owners would

guarantee

the players a percentage of every dollar they earned, and the

players in return agreed that each team would be subject to a

soft

cap on the amount of salaries it would pay to the players. The

owners also provided:

- A guarantee that the league would maintain 253 players even

if

the number of franchises would be reduced;

- $500,000 in licensing revenue; and

- An increase in the minimum salary to $40,000

By 1984, the average player salary had increased to $275,000 and

the

stability of the league improved. Individual players were

featured

in the league’s marketing strategies, further fueling the

league’s

growth

Junior Bridgeman antitrust suit filed (settled in 1988)

Junior Bridgeman became NBPA president in 1985, and the players

strived for more. As the CBA neared its conclusion in 1988, the

players voiced their discontent with portions of the salary cap,

restricted free agency, and the college draft system. Once

again,

the players looked to the federal courts for relief, as the

“Bridgeman antitrust suit” was filed in federal court. Following

a

favorable preliminary ruling for the players, the owners again

opted

to avoid a risky litigation. The parties shook hands on a new

six-year collective bargaining agreement that called for:

- The elimination of the right of first refusal after a player

completes his second contract, with unrestricted free agency

for

veteran players;

- Inclusion of five-year veterans who finished their careers

prior

to 1965 in the pension plan; and

- A reduction of the college draft to three rounds in 1988 and

two

rounds in 1989

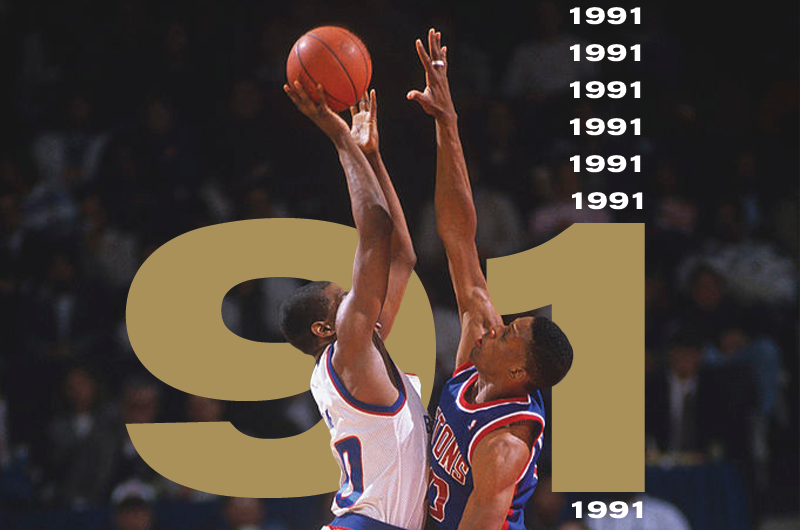

NBA alleged violation of its revenue sharing obligation

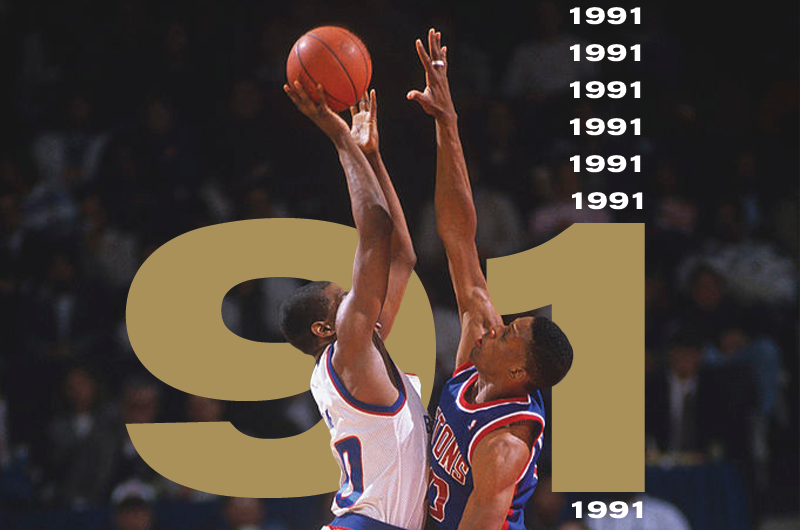

Tensions arose again in 1991, when the NBPA alleged that the

owners

were violating the revenue sharing agreement by underreporting

their

income, and thereby artificially depressing the Salary Cap and

the

players’ guaranteed share of revenues. In a major grievance, the

players claimed the owners were improperly excluding revenues

relating to luxury suite and arena signage rentals,

international

television broadcasts, related party transactions, and other

sources. The dispute severely dampened the degree of trust the

parties felt with each other. With a potentially damaging and

drawn

out litigation on the horizon, the NBA reached a settlement with

the

NBPA valued at $62 million for the players. Isiah Thomas, who

had

earlier taken over the presidency from Alex English, presided at

that time.

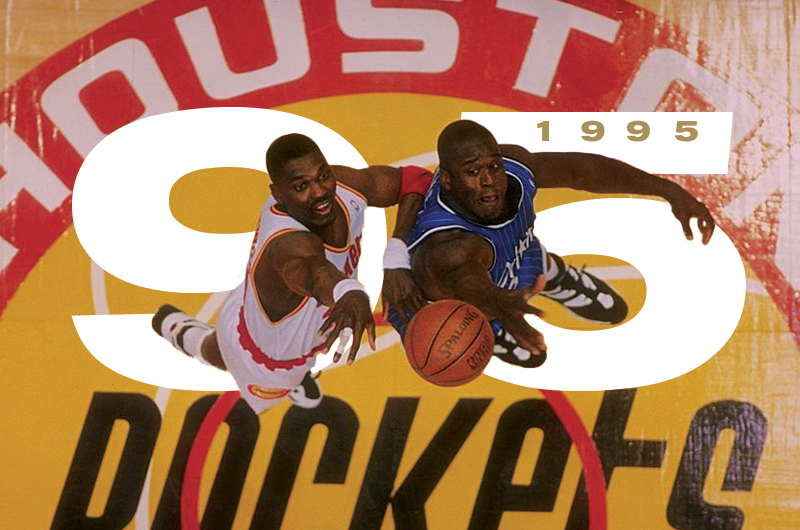

Players consider decertification in facing the first ever

lockout

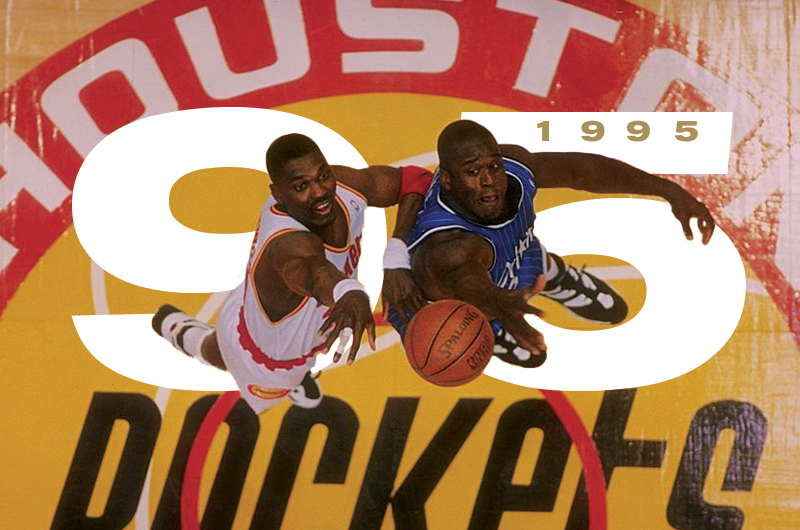

Following the 1995 NBA Finals, for the first time ever, the

owners

imposed a lockout, shutting down the business. No basketball

activity took place during the summer of 1995, as the union

fought

two major battles – one with the owners, and the other among

itself.

The owners were holding firm to their position that the players

had

to accept concessions and tighten up the salary system. The

players

differed among themselves as to the best way to fight back.

Seeing

that the chances were slim of reaching a fair agreement without

having to endure a long work stoppage, a large group of players

felt

that it would be best to decertify the union, and proceed in

court

against the owners; they claimed that the antitrust laws were

the

best weapon to stop the owners from imposing restrictive terms

like

a tougher salary cap and free agency system. The players

believed

they could get a court to order the lockout unlawful, and play

while

the claims were litigated. Other players were unsure and uneasy

about the concept of decertification. Nonetheless, the threat of

decertification was a very real one. Faced with the prospect of

another litigation and the uncertainty brought about by the

proposed

decertification, the owners agreed to modify their harsh

demands,

and a new agreement was reached. The agreement, negotiated under

President Buck Williams, contained elements for both sides. For

the

owners, the agreement eliminated or softened many of the

multitude

of salary cap exceptions that had allowed the teams to amass

large

payrolls. It also contained a rookie wage scale, with a pre-set

salary range. In addition, the allowable percentage increase in

multi-year contracts was reduced from 30% to 20%, and limits

were

placed on the length of a contract. Still, for the players, the

agreement retained the all-important Larry Bird exception,

allowing

a team to exceed the Cap to re-sign its own free agent. It also

eliminated entirely the concept of restricted free agency, with

unrestricted free agency granted to all players after their

contract

expired. In addition, in response to the earlier revenue sharing

dispute, the parties agreed to include new sources of revenue in

the

revenue sharing formula.

Second lockout; owners seek hard cap

By the 1997-98 season the approximately 400 NBA players were

collectively earning $1 billion in salaries and benefits. In

March

of 1998, the owners exercised their option to terminate the

collective bargaining agreement at the conclusion of the season.

When the players again refused to accept unfavorable terms, the

league again locked the players out, shutting down the business

on

July 1, 1998. This time, the shutdown lasted far longer. With

the

owners seeking a “hard” salary cap that would lead to the

elimination of guaranteed contracts and the virtual elimination

of

the “middle class” of NBA earners, the players dug in and

refused to

concede. With no new agreement on the horizon, the League first

canceled the pre-season, then cancelled the first two months of

the

season, and then announced the cancellation of the All-Star

Game.

Finally, in January 1999, after a six-month lockout and on the

eve

of the “drop dead” date to end the season, the parties reached

an

agreement. Games began in early February, with each team playing

a

shortened 50 game schedule. The new agreement, negotiated under

President Patrick Ewing, did not include a hard cap, and instead

featured a series of trade-offs that the owners hoped would work

to

keep salaries down. Many of these terms are discussed below in

the

section on the NBA salary system. As it turned out, under the

1999

agreement, the players enjoyed an 80% increase in salaries and

benefits. In 2004-05, the last year of the 1999 CBA, the players

earned approximately $1.8 billion in salaries and revenues. The

average player salary rose to well over $4.5 million, and the

median

salary experienced unprecedented growth, doubling so that more

than

half of all NBA players earned at least $2.8 million.

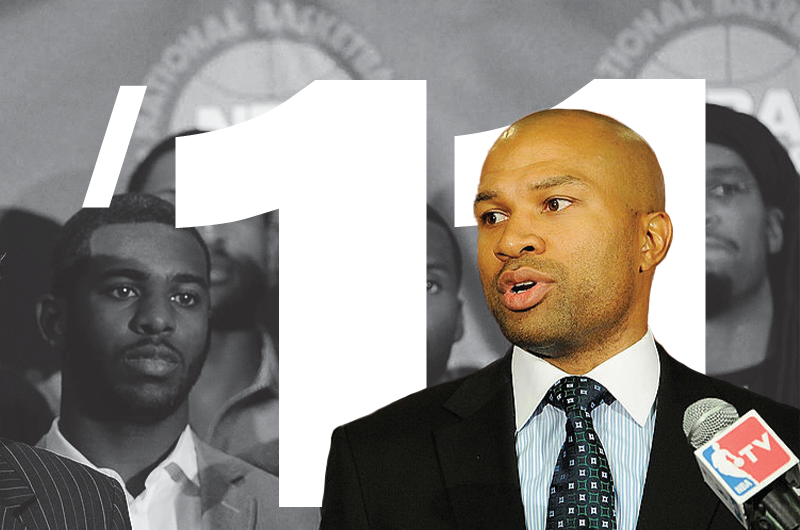

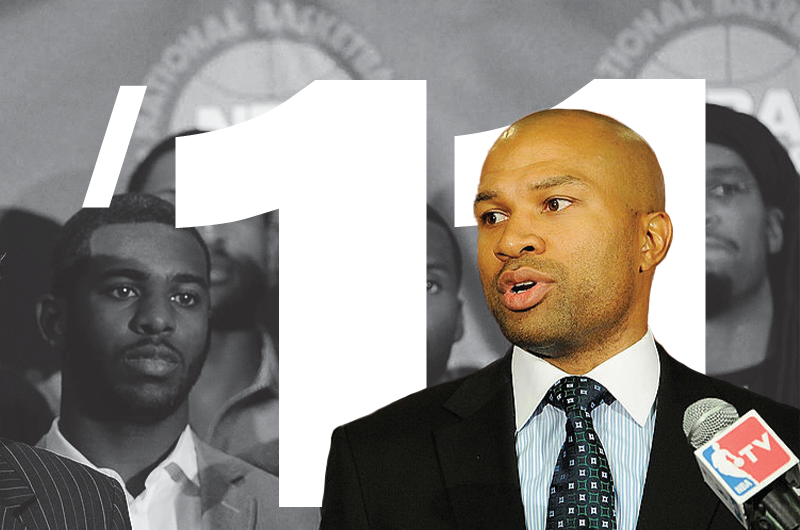

Another lockout; preservation of the soft cap and guaranteed

contracts

In the summer of 2009, Commissioner Stern and the owners informed

the

NBPA that they would not exercise the option to extend the 2005

agreement for a seventh season and that the agreement would

officially expire on June 30, 2011.Negotiations, which had begun

in

the summer of 2009, intensified during the 2010-11 season. As

they

had done in 1999, the NBA owners demanded significant, across

the

board rollbacks including 40% reductions in the value of all

existing and future contracts. In order to obtain this harsh

economic result, the NBA proposed a series of draconian system

changes including a hard salary cap and severe restrictions on

players’ ability to negotiate for guaranteed contracts. With no

negotiated settlement in sight, the NBA owners imposed a lockout

on

July 1, 2011 immediately upon the expiration of the agreement.

For

the second time in NBA history, preseason and ultimately regular

season games were cancelled. In November 2011, the Players

Association disclaimed interest, relinquishing its status as the

players’ exclusive collective bargaining representative.

Antitrust

lawsuits were filed on behalf of players in California and

Minnesota

challenging the legality of the lockout. Faced with the

cancellation

of the season and possibly antitrust liability, the owners chose

to

settle the antitrust suits with the players. The players voted

to

re-form the union and a new CBA was signed on December 8, 2011,

161

days after the lockout began.

Union selects new leadership

Under President Chris Paul’s leadership, the NBPA Executive

Committee

and Board of Player Representatives elected Michele Roberts as

the

union’s new executive director. Roberts became the first woman

to

head a major professional sports union in North America.

Michele Roberts Re-elected as Executive Director of the NBPA

Michele Roberts was re-elected as Executive Director of the

National

Basketball Players Association (NBPA) at the 2018 annual summer

meeting of the Board of NBA Player Representatives. The Board of

Player Representatives and the Executive Committee voted

unanimously

to approve another 4-year term for Ms. Roberts.

“Our goal when we hired Michele was to take back our union,” said

NBPA President Chris Paul. “With her leadership and guidance, we

have not only accomplished that but we have also established the

NBPA as one of the strongest and most active unions in all of

professional sports. She is truly an invaluable asset and I am

thrilled that we will get to continue our work together.”